Tumores suprarrenales: El incidentaloma suprarrenal es un problema clínico de detección frecuente y la intervención temprana ofrece el mejor pronóstico.

Autor(es): Dres. Vanessa W S Ng, Ronald C W, Wing-Yee So, Kai Chow Choi, Alice P. S. Kong, Clive S. Cockram, Chun-Chung Chow Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2017-2020

Resumen

|

Los incidentalomas suprarrenales son tumores suprarrenales descubiertos en forma accidental al realizar una imagen radiológica que indicada por otras razones. La mayoría son benignos y no funcionales. Sin embargo, las lesiones suprarrenales funcionales secretan exceso de hormonas suprarrenales, tales como el cortisol, la aldosterona, las catecolaminas, las hormonas sexuales o una combinación de hormonas suprarrenales. Representan una significativa proporción de casos, con un aumento de la morbilidad si no son tratados. Las lesiones suprarrenales malignas son poco comunes e incluyen los cánceres primarios suprarrenales, las metástasis suprarrenales u otras neoplasias malignas poco frecuentes. Aunque el cáncer suprarrenal primario es poco frecuente en la población general, cuando el cáncer es pequeño y todavía está confinado al lecho suprarrenal la intervención temprana ofrece el mejor pronóstico. Por ello es importante evaluar el estado funcional y el potencial de malignidad de cada descubrimiento de lesión adrenal.

Objetivo

Analizar las características clínicas de los pacientes con incidentalomas suprarrenales que consultaron en un centro endocrinológico de tercer nivel de Hong Kong.

Métodos

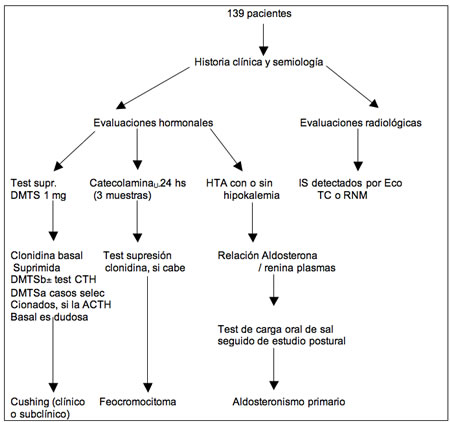

Revisión retrospectiva de 139 casos de incidentalomas suprarrenales que fueron referidos al Hospital Endocrine Centre of the Prince of Wales entre el 1 de junio de 2000 y el 31 de mayo de 2007. Se revisaron detalladamente la historia de los pacientes, los hallazgos del examen físico y los síntomas y signos relacionados con la hipersecreción hormonal o el cáncer. También se registraron las indicaciones clínicas para la realización de estudios radiológicos para el diagnóstico por imágenes.

Resultados

Sesenta y un pacientes (43,9%) presentaban adenomas suprarrenales funcionales benignos, 52 (37,4%) tenían lesiones funcionales y 15 (10,8%), lesiones malignas suprarrenales. Los 11 restantes (7,9%) presentaban diversas enfermedades suprarrenales. Entre los pacientes con lesiones funcionales, 27 (19,4%) tenían lesiones que secretaban exceso de cortisol, 12 (8,6%) tenían lesiones que secretaban aldosterona, 12 (8,6%), lesiones productoras de catecolaminas y, 1 (0,7%) paciente presentó una lesión que demostró segregar un exceso de cortisol y aldosterona. En la presentación, solo 5 de los 27 pacientes con incidentaloma suprarrenal secretor de cortisol tenían síntomas o signos de niveles elevados de cortisol.

CatecolaminaU: catecolamina urinaria; DMTS: dexametasona; DMTSb: dosis baja de DMTS; DMTSa: dosis elevada de EMTS; Eco: ecografía; HTA: hipertensión arterial; IS: incidentaloma suprarrenal; TC: tomografía computarizada; RNM: resonancia nuclear magnética; ACTH: corticotrofina; CTH: Hormona liberadora de corticotrofina;

Comentarios

Los incidentalomas suprarrenales no son raros. Tienen una prevalencia de 3% a 4% en las series de tomografía computarizada abdominal y son edad dependiente. Son poco comunes en personas menores de 30 años, con una prevalencia estimada de 0,2%, pero la prevalencia aumenta a 7% en las personas de 70 años o más. En este estudio, la mayoría de los pacientes estaba en la cuarta a octava década de la vida, con un predominio del sexo femenino. Este patrón de distribución por edades refleja el mayor número de investigaciones radiológicas que se hace en personas mayores y la mayor prevalencia de nódulos suprarrenales a medida que la edad es mayor. El predominio del sexo femenino probablemente refleja la distribución por sexo de los pacientes sometidos a procedimientos de imagen en Hong Kong, porque en series anteriores de autopsias no se halló ninguna diferencia en la prevalencia con respecto al sexo.

En este estudio, los incidentalomas suprarrenales funcionales representaron el 37,4% de la cohorte, siendo el más común el adenoma secretor de cortisol. Los pacientes con síndrome de Cushing subclínico tienen adenomas con secreción autónoma de cortisol pero no presentan los signos y síntomas típicos del síndrome de Cushing manifiesto. Sin embargo, pueden sufrir los efectos perjudiciales del exceso de secreción sutil y continua de cortisol, incluyendo la resistencia a la insulina, la diabetes mellitus, la hipertensión, la osteoporosis, la obesidad y las complicaciones trombóticas. Entre los pacientes de este estudio con síndrome de Cushing subclínico, la hipertensión, la diabetes o la obesidad mejoraron con el tratamiento quirúrgico exitoso.

La causa más común de hipertensión secundaria es el aldosteronismo primario, el cual representa hasta el 12% de todos los pacientes hipertensos. En la presente cohorte, el aldosteronismo primario correspondió al 8,6% de los casos. Para los pacientes con adenomas productores de aldosterona, la extirpación quirúrgica con éxito dio lugar a la normalización de la hipopotasemia y un mejor control de la presión arterial. Por otra parte, algunos de estos pacientes pudieron suspender la medicación antihipertensiva debido a la normalización de su presión arterial. Estos resultados destacan la importancia de descartar el aldosteronismo primario, una causa tratable de hipertensión secundaria, en todos los pacientes hipertensos con incidentaloma suprarrenal.

Doce pacientes tenían un feocromocitoma confirmado. Siete pacientes eran normotensos y 6 eran asintomáticos. Clínicamente, el feocromocitoma silente podría ser un trastorno letal, con una evolución impredecible. Los paroxismos letales y la mortalidad perioperatoria pueden presentarse hasta en el 50% de los pacientes con un feocromocitoma reconocido. Según los autores, esto pone de relieve la necesidad de excluir a los feocromocitomas en todos los pacientes con incidentaloma suprarrenal, incluso si el paciente es normotenso o asintomático, sobre todo antes de pensar en la biopsia o la cirugía suprarrenal.

El cáncer suprarrenal primario y las metástasis suprarrenales son los dos tumores malignos suprarrenales más comunes. Aunque el cáncer suprarrenal primario es extremadamente raro, con una incidencia de 1 a 2 casos por 1 millón de personas, se asocia con una tasa elevada de mortalidad y un pronóstico muy malo. Con el uso común de las exploraciones radiológicas, la detección del cáncer suprrarenal primario es cada vez más frecuente ya que es descubierto como un incidentaloma. Los autores sostienen que la única posibilidad de cura y supervivencia a largo plazo la brindan el reconocimiento y la resección quirúrgica tempranos, basados en los dos pacientes del presente estudio que presentaban cáncer suprarrenal primario en estadio I.

Los autores mencionan dos limitaciones importantes en su estudio: el tamaño pequeño de la muestra y el reclutamiento de pacientes que se atendían en un centro terciario de referencia. Estas limitaciones, dicen, pueden explicar porqué en este grupo de pacientes estudiados se detectaron los incidentalomas suprarrenales más funcionales y malignos en comparación con la población general, considerando que estos pacientes eran personas con casos más complicados y múltiples comorbilidades. Sin embargo, acotan, “las series clínicas de diversos centros de referencia de tercer nivel de todo el mundo confirmaron nuestro hallazgo: los incidentalomas suprarrenales funcionales y malignos no son raros.”

Conclusión

El incidentaloma suprarrenal es un hallazgo clínico común. Los incidentalomas suprarrenales funcionales y malignos pueden ser detectados en una etapa anterior durante las evaluaciones hormonales y radiológicas, lo que ofrece una oportunidad para su manejo ulterior.

Artículos relacionados

Artículos relacionados

Traducción y resumen: Ramón Díaz-Alersi vía © REMI, Dr. Rafael Perez Garcia vía Emergency & Critical Care

Referencias bibliográficas

1. Abu-Alfa AK, Younes A. Tumor lysis syndrome and acute kidney injury: evaluation, prevention, and management. Am J Kidney Dis 2010;55:Suppl 3:S1-S13.

2. Cairo MS, Coiffier B, Reiter A, Younes A. Recommendations for the evaluation of risk and prophylaxis of tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) in adults and children with malignant diseases: an expert TLS panel consensus. Br J Haematol 2010;149:578-86.

3. Gertz MA. Managing tumor lysis syndrome in 2010. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;51: 179-80.

4. Magrath IT, Semawere C, Nkwocha J. Causes of death in patients with Burkitt’s lymphoma — the role of supportive care in overall management. East Afr Med J 1974;51:623-32.

5. Krishnan G, D’Silva K, Al-Janadi A. Cetuximab-related tumor lysis syndrome in metastatic colon carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2406-8.

6. Noh GY, Choe DH, Kim CH, Lee JC.

Fatal tumor lysis syndrome during radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:6005- 6.

7. Godoy H, Kesterson JP, Lele S. Tumor lysis syndrome associated with carboplatin and paclitaxel in a woman with recurrent endometrial cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;109:254.

8. Joshita S, Yoshizawa K, Sano K, et al. A patient with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib tosylate showed massive tumor lysis with avoidance of tumor lysis syndrome. Intern Med 2010;49:991-4.

9. Coiffier B, Altman A, Pui CH, Younes A, Cairo MS. Guidelines for the management of pediatric and adult tumor lysis syndrome: an evidence-based review. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2767-78. [Erratum, J Clin Oncol 2010;28:708.]

10. Cairo MS, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol 2004;127:3-11.

11. Levin A, Warnock DG, Mehta RL, et al. Improving outcomes from acute kidney injury: report of an initiative. Am J Kidney Dis 2007;50:1-4.

12. Hochberg J, Cairo MS. Rasburicase:future directions in tumor lysis management. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2008;8:1595-604.

13. Howard SC, Ribeiro RC, Pui C-H. Acute complications. In: Pui C-H, ed. Childhood leukemias. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2006:709-49.

14. Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1811-21. [Erratum, N Engl J Med 2010;362:2235.]

15. Shimada M, Johnson RJ, May WS Jr, et al. A novel role for uric acid in acute kidney injury associated with tumour lysis The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by Daniel Flichtentrei on May 16, 2011. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24:2960-4.

16. Ejaz AA, Mu W, Kang DH, et al. Could uric acid have a role in acute renal failure? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:16-21.

17. Hijiya N, Metzger ML, Pounds S, et al. Severe cardiopulmonary complications consistent with systemic inflammatory response syndrome caused by leukaemia cell lysis in childhood acute myelomonocytic or monocytic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2005;44:63-9.

18. Nakamura M, Oda S, Sadahiro T, et al. The role of hypercytokinemia in the pathophysiology of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) and the treatment with continuous hemodiafiltration using a polymethylmethacrylate membrane hemofilter (PMMACHDF). Transfus Apher Sci 2009;40:41-7.

19. Soares M, Feres GA, Salluh JI. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction in patients with acute tumor lysis syndrome. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64:479-81.

20. LaRosa C, McMullen L, Bakdash S, et al. Acute renal failure from xanthine nephropathy during management of acute leukemia. Pediatr Nephrol 2007;22:132-5.

21. Bouropoulos C, Vagenas N, Klepetsanis PG, Stavropoulos N, Bouropoulos N. Growth of calcium oxalate monohydrate on uric acid crystals at sustained supersaturation. Cryst Res Technol 2004;39:699- 704.

22. Grases F, Sanchis P, Isern B, Perelló J, Costa-Bauzá A. Uric acid as inducer of calcium oxalate crystal development. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2007;41:26-31.

23. Greene ML, Fujimoto WY, Seegmiller JE. Urinary xanthine stones — a rare complication of allopurinol therapy. N Engl J Med 1969;280:426-7.

24. Beshensky AM, Wesson JA, Worcester EM, et al. Effects of urinary macromolecules on hydroxyapatite crystal formation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:2108-16.

25. Wesson JA, Worcester EM, Wiessner JH, Mandel NS, Kleinman JG. Control of calcium oxalate crystal structure and cell adherence by urinary macromolecules. Kidney Int 1998;53:952-7.

2. Cairo MS, Coiffier B, Reiter A, Younes A. Recommendations for the evaluation of risk and prophylaxis of tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) in adults and children with malignant diseases: an expert TLS panel consensus. Br J Haematol 2010;149:578-86.

3. Gertz MA. Managing tumor lysis syndrome in 2010. Leuk Lymphoma 2010;51: 179-80.

4. Magrath IT, Semawere C, Nkwocha J. Causes of death in patients with Burkitt’s lymphoma — the role of supportive care in overall management. East Afr Med J 1974;51:623-32.

5. Krishnan G, D’Silva K, Al-Janadi A. Cetuximab-related tumor lysis syndrome in metastatic colon carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2406-8.

6. Noh GY, Choe DH, Kim CH, Lee JC.

Fatal tumor lysis syndrome during radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:6005- 6.

7. Godoy H, Kesterson JP, Lele S. Tumor lysis syndrome associated with carboplatin and paclitaxel in a woman with recurrent endometrial cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;109:254.

8. Joshita S, Yoshizawa K, Sano K, et al. A patient with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib tosylate showed massive tumor lysis with avoidance of tumor lysis syndrome. Intern Med 2010;49:991-4.

9. Coiffier B, Altman A, Pui CH, Younes A, Cairo MS. Guidelines for the management of pediatric and adult tumor lysis syndrome: an evidence-based review. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2767-78. [Erratum, J Clin Oncol 2010;28:708.]

10. Cairo MS, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol 2004;127:3-11.

11. Levin A, Warnock DG, Mehta RL, et al. Improving outcomes from acute kidney injury: report of an initiative. Am J Kidney Dis 2007;50:1-4.

12. Hochberg J, Cairo MS. Rasburicase:future directions in tumor lysis management. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2008;8:1595-604.

13. Howard SC, Ribeiro RC, Pui C-H. Acute complications. In: Pui C-H, ed. Childhood leukemias. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2006:709-49.

14. Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1811-21. [Erratum, N Engl J Med 2010;362:2235.]

15. Shimada M, Johnson RJ, May WS Jr, et al. A novel role for uric acid in acute kidney injury associated with tumour lysis The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by Daniel Flichtentrei on May 16, 2011. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24:2960-4.

16. Ejaz AA, Mu W, Kang DH, et al. Could uric acid have a role in acute renal failure? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:16-21.

17. Hijiya N, Metzger ML, Pounds S, et al. Severe cardiopulmonary complications consistent with systemic inflammatory response syndrome caused by leukaemia cell lysis in childhood acute myelomonocytic or monocytic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2005;44:63-9.

18. Nakamura M, Oda S, Sadahiro T, et al. The role of hypercytokinemia in the pathophysiology of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) and the treatment with continuous hemodiafiltration using a polymethylmethacrylate membrane hemofilter (PMMACHDF). Transfus Apher Sci 2009;40:41-7.

19. Soares M, Feres GA, Salluh JI. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction in patients with acute tumor lysis syndrome. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64:479-81.

20. LaRosa C, McMullen L, Bakdash S, et al. Acute renal failure from xanthine nephropathy during management of acute leukemia. Pediatr Nephrol 2007;22:132-5.

21. Bouropoulos C, Vagenas N, Klepetsanis PG, Stavropoulos N, Bouropoulos N. Growth of calcium oxalate monohydrate on uric acid crystals at sustained supersaturation. Cryst Res Technol 2004;39:699- 704.

22. Grases F, Sanchis P, Isern B, Perelló J, Costa-Bauzá A. Uric acid as inducer of calcium oxalate crystal development. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2007;41:26-31.

23. Greene ML, Fujimoto WY, Seegmiller JE. Urinary xanthine stones — a rare complication of allopurinol therapy. N Engl J Med 1969;280:426-7.

24. Beshensky AM, Wesson JA, Worcester EM, et al. Effects of urinary macromolecules on hydroxyapatite crystal formation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:2108-16.

25. Wesson JA, Worcester EM, Wiessner JH, Mandel NS, Kleinman JG. Control of calcium oxalate crystal structure and cell adherence by urinary macromolecules. Kidney Int 1998;53:952-7.

26. Finlayson B. Physicochemical aspects of urolithiasis. Kidney Int 1978;13:344-60.

27. Pais VM Jr, Lowe G, Lallas CD, Preminger GM, Assimos DG. Xanthine urolithiasis. Urology 2006;67(5):1084.e9-1084. e11.

28. Howard SC, Pui CH. Pitfalls in predicting tumor lysis syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma 2006;47:782-5.

29. Cheson BD. Etiology and management of tumor lysis syndrome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2009;7:263-71.

30. Gemici C. Tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2738-9.

31. Huang WS, Yang CH. Sorafenib induced tumor lysis syndrome in an advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patient. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4464-6.

32. Keane C, Henden A, Bird R. Catastrophic tumour lysis syndrome following single dose of imatinib. Eur J Haematol 2009;82:244-5.

33. Cairo MS, Gerrard M, Sposto R, et al. Results of a randomized international study of high-risk central nervous system B non-Hodgkin lymphoma and B acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children and adolescents. Blood 2007;109:2736-43.

34. The VA/NIH Acute Renal Failure Trail Network. Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med 2008;359:7-20. [Erratum, N Engl J Med 2009;361:2391.]

35. Montesinos P, Lorenzo I, Martin G, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: identification of risk factors and development of a predictive model. Haematologica 2008;93:67- 74.

36. Mato AR, Riccio BE, Qin L, et al. A predictive model for the detection of tumor lysis syndrome during AML induction therapy. Leuk Lymphoma 2006;47:877-83.

37. Truong TH, Beyene J, Hitzler J, et al. Features at presentation predict children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia at low risk for tumor lysis syndrome. Cancer 2007;110:1832-9.

38. Feusner JH, Ritchey AK, Cohn SL, Billett AL. Management of tumor lysis syndrome: need for evidence-based guidelines. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5657-8.

39. Conger JD, Falk SA. Intrarenal dynamics in the pathogenesis and prevention of acute urate nephropathy. J Clin Invest 1977;59:786-93.

40. Pui CH, Mahmoud HH, Wiley JM, et al. Recombinant urate oxidase for the prophylaxis or treatment of hyperuricemia in patients with leukemia or lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:697-704.

41. Goldman SC, Holcenberg JS, Finklestein JZ, et al. A randomized comparison between rasburicase and allopurinol in children with lymphoma or leukemia at high risk for tumor lysis. Blood 2001;97:2998- 3003.

42. St. Jude Leukemia/Lymphoma Board. Tumor lysis syndrome focusing on hyperphosphatemia. November 13, 2007. (http: //www.cure4kids.org/private/lectures/ppt1468/C4K-1454-0MC-Tumor-Lysis.pdf.) 43. Sundy JS, Becker MA, Baraf HS, et al. Reduction of plasma urate levels following treatment with multiple doses of pegloticase (polyethylene glycol-conjugated uricase) in patients with treatment-failure gout: results of a phase II randomized study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2882-91.

44. Jeha S, Kantarjian H, Irwin D, et al. Efficacy and safety of rasburicase, a recombinant urate oxidase (Elitek), in the management of malignancy-associated hyperuricemia in pediatric and adult patients:final results of a multicenter compassionate use trial. Leukemia 2005;19:34-8.

27. Pais VM Jr, Lowe G, Lallas CD, Preminger GM, Assimos DG. Xanthine urolithiasis. Urology 2006;67(5):1084.e9-1084. e11.

28. Howard SC, Pui CH. Pitfalls in predicting tumor lysis syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma 2006;47:782-5.

29. Cheson BD. Etiology and management of tumor lysis syndrome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2009;7:263-71.

30. Gemici C. Tumor lysis syndrome in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2738-9.

31. Huang WS, Yang CH. Sorafenib induced tumor lysis syndrome in an advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patient. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4464-6.

32. Keane C, Henden A, Bird R. Catastrophic tumour lysis syndrome following single dose of imatinib. Eur J Haematol 2009;82:244-5.

33. Cairo MS, Gerrard M, Sposto R, et al. Results of a randomized international study of high-risk central nervous system B non-Hodgkin lymphoma and B acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children and adolescents. Blood 2007;109:2736-43.

34. The VA/NIH Acute Renal Failure Trail Network. Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med 2008;359:7-20. [Erratum, N Engl J Med 2009;361:2391.]

35. Montesinos P, Lorenzo I, Martin G, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: identification of risk factors and development of a predictive model. Haematologica 2008;93:67- 74.

36. Mato AR, Riccio BE, Qin L, et al. A predictive model for the detection of tumor lysis syndrome during AML induction therapy. Leuk Lymphoma 2006;47:877-83.

37. Truong TH, Beyene J, Hitzler J, et al. Features at presentation predict children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia at low risk for tumor lysis syndrome. Cancer 2007;110:1832-9.

38. Feusner JH, Ritchey AK, Cohn SL, Billett AL. Management of tumor lysis syndrome: need for evidence-based guidelines. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5657-8.

39. Conger JD, Falk SA. Intrarenal dynamics in the pathogenesis and prevention of acute urate nephropathy. J Clin Invest 1977;59:786-93.

40. Pui CH, Mahmoud HH, Wiley JM, et al. Recombinant urate oxidase for the prophylaxis or treatment of hyperuricemia in patients with leukemia or lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:697-704.

41. Goldman SC, Holcenberg JS, Finklestein JZ, et al. A randomized comparison between rasburicase and allopurinol in children with lymphoma or leukemia at high risk for tumor lysis. Blood 2001;97:2998- 3003.

42. St. Jude Leukemia/Lymphoma Board. Tumor lysis syndrome focusing on hyperphosphatemia. November 13, 2007. (http: //www.cure4kids.org/private/lectures/ppt1468/C4K-1454-0MC-Tumor-Lysis.pdf.) 43. Sundy JS, Becker MA, Baraf HS, et al. Reduction of plasma urate levels following treatment with multiple doses of pegloticase (polyethylene glycol-conjugated uricase) in patients with treatment-failure gout: results of a phase II randomized study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2882-91.

44. Jeha S, Kantarjian H, Irwin D, et al. Efficacy and safety of rasburicase, a recombinant urate oxidase (Elitek), in the management of malignancy-associated hyperuricemia in pediatric and adult patients:final results of a multicenter compassionate use trial. Leukemia 2005;19:34-8.

45. Giraldez M, Puto K. A single, fixed dose of rasburicase (6 mg maximum) for treatment of tumor lysis syndrome in adults. Eur J Haematol 2010;85:177-9.

46. Knoebel R, Lo M, Crank C. Evaluation of a low, weight-based dose of rasburicase in adult patients for the treatment or prophylaxis of tumor lysis syndrome. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2010 March 23 (Epub ahead of print).

46. Knoebel R, Lo M, Crank C. Evaluation of a low, weight-based dose of rasburicase in adult patients for the treatment or prophylaxis of tumor lysis syndrome. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2010 March 23 (Epub ahead of print).

47. Bellinghieri G, Santoro D, Savica V. Emerging drugs for hyperphosphatemia. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2007;12:355-65.

48. Tonelli M, Pannu N, Manns B. Oral phosphate binders in patients with kidney failure. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1312-24.

48. Tonelli M, Pannu N, Manns B. Oral phosphate binders in patients with kidney failure. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1312-24.

49. Prié D, Friedlander G. Genetic disorders of renal phosphate transport. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2399- 409.

50. Gutzwiller JP, Schneditz D, Huber AR, et al. Estimating phosphate removal in haemodialysis: an additional tool to quantify dialysis dose. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;17:1037-44.

50. Gutzwiller JP, Schneditz D, Huber AR, et al. Estimating phosphate removal in haemodialysis: an additional tool to quantify dialysis dose. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;17:1037-44.

51. Tan HK, Bellomo R, M’Pis DA, Ronco C. Phosphatemic control during acute renal failure: intermittent hemodialysis versus continuous hemodiafiltration. Int J Artif Organs 2001;24:186-91.

52. Pui CH, Jeha S, Irwin D, Camitta B. Recombinant urate oxidase (rasburicase) in the prevention and treatment of malignancy- associated hyperuricemia in pediatric and adult patients: results of a compassionate-use trial. Leukemia 2001;15:1505-9.

52. Pui CH, Jeha S, Irwin D, Camitta B. Recombinant urate oxidase (rasburicase) in the prevention and treatment of malignancy- associated hyperuricemia in pediatric and adult patients: results of a compassionate-use trial. Leukemia 2001;15:1505-9.

53. Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2730-41.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario